With a low-lying, typhoon-battered coastline and inland regions faced with desertification, melting glaciers, and sweltering summer heat, China would seem like it has plenty to fear from climate change.

Nevertheless, researchers in 2019 looking into how the Chinese public viewed the issue found that they were relatively unconcerned.

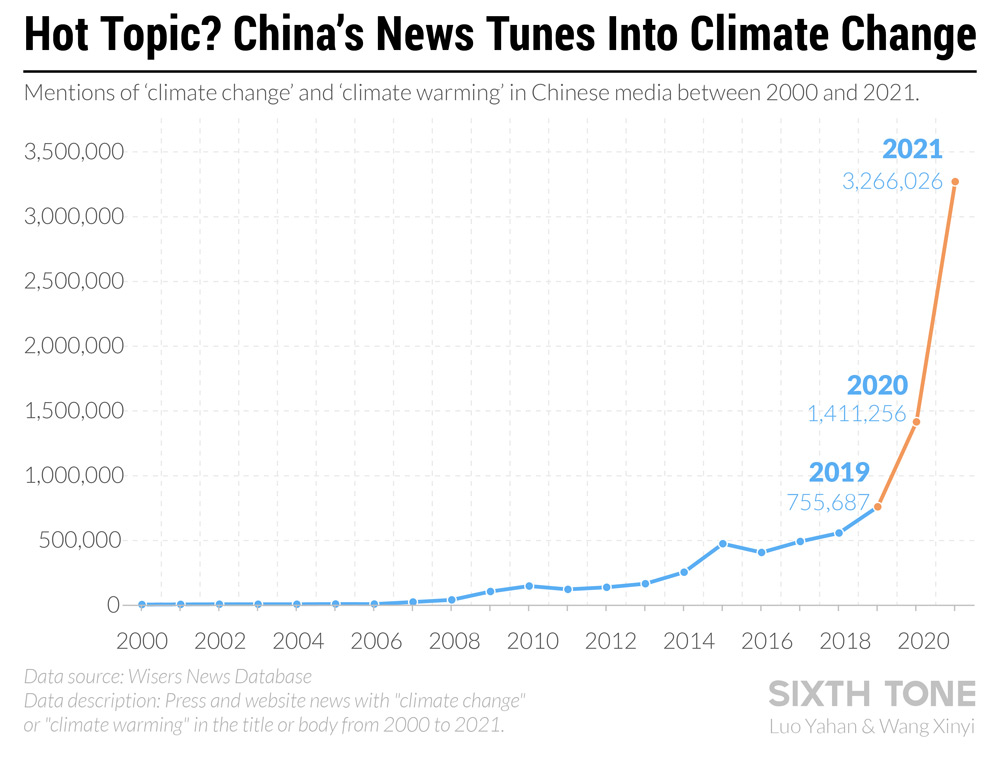

But the past year has brought big shifts. Climate change is increasingly a topic of discussion in China. Sixth Tone’s analysis of a Chinese news database that summarized how often related keywords appeared in media articles showed that such mentions have skyrocketed. In 2019, fewer than 800,000 articles on the subject were published in Chinese media. This figure increased to nearly 1.5 million in 2020 and over 3.2 million this year.

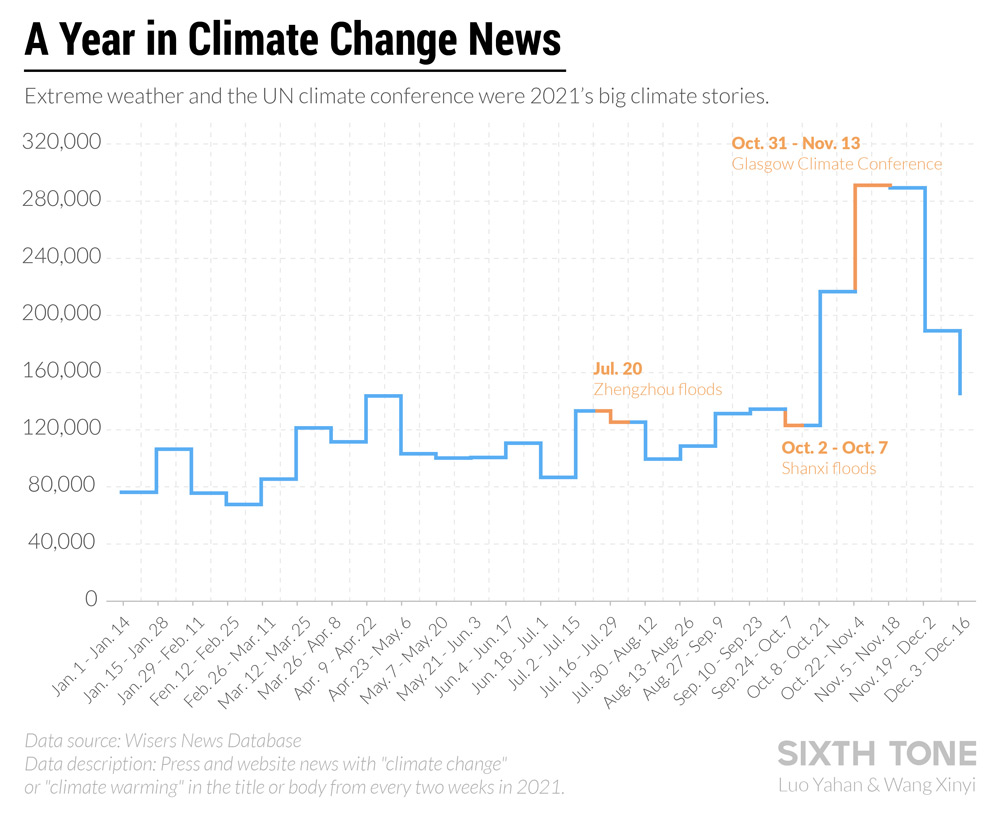

In part, this was due to political events. In late 2020, President Xi Jinping announced ambitious climate goals for the country. A year later, the climate summit in Glasgow, U.K., dominated the news. But perhaps the biggest driver of attention was China’s year of extreme weather.

Historic rains fell in the central Chinese province of Henan in July, with its capital Zhengzhou recording an average year’s worth of precipitation in just three days. The resulting floods killed at least 302 people and caused direct economic losses of over 133 billion yuan ($20.9 billion) across the province. In October, the northern Shanxi province was hit with heavy rain, damaging many historic buildings.

The devastation reminded governments around the country of what may await them, spurring them to reassess how vulnerable their municipalities are to increasingly common extreme weather events. Temperatures in China have risen faster than the global average, according to a government-backed report on climate change published in August. Researchers predict that precipitation patterns in large parts of China will feature more intense showers. Sea levels are rising, and droughts could well become more frequent.

Since 2013, the Chinese government has taken some steps to address climate risks, including pledging more financial support to climate-proof certain crucial urban infrastructure projects and tasking 27 cities with conducting regional climate adaptation pilots. But progress is limited, says Chen Aiping, regional director of Global Center on Adaptation’s China Office. “The awareness of adaptation is at a very early stage in China,” she tells Sixth Tone.

Cities, home to an ever-growing majority of China’s population, rarely assess climate risks during construction projects, according to a report released in December as part of the China-U.K. Climate Change Risk Assessment Project. Such lack of consideration is dangerous because important public facilities end up built on the wrong sites, says Zhang Weijun, founder of Ewaters Environmental Science & Technology, a Shanghai-based water solutions consultancy that is working with several Chinese cities to map flood risks.

People pass by a subway station entrance on a flooded street in Zhengzhou, Henan province, July 22, 2021. People Visual

Using public data, Ewaters reconstructed Zhengzhou’s floods and found that many of the city’s key public facilities, such as subways and hospitals, are located in flood-prone weak spots. This had costly consequences. Notably, Fuwai Central China Cardiovascular Hospital, one of the city’s best, was hit hard because it is situated in a low-lying area. When flooding began on July 20, water quickly submerged its entrance hall. Over 5,000 people were trapped in the hospital, power was cut, and medical equipment stored underground was damaged. Evacuating people took three days, and the hospital could not reopen until two weeks later. According to preliminary calculations, the hospital suffered an estimated 1.4 billion yuan in damages.

“Our current problem is that when building a city, there is a lack of analysis and assessment of flood risks — we don’t really know whether a place might be submerged,” Zhang tells Sixth Tone.

Chinese authorities say they want to improve cities’ resilience to extreme weather. But how remains unanswered. Considering how poor disaster management and preventative measures exacerbated Zhengzhou’s floods, Chinese cities should ponder such aspects first, says Zhai Guofang, professor of disaster reduction at Nanjing University’s School of Architecture and Urban Planning. Cities should invest more in emergency shelters and should delineate which areas are more and less important so they can strategically choose how to deal with “limit-exceeding” stormwaters, he tells Sixth Tone.

Chen, of the Global Center on Adaptation, says China should continue to invest in adaptation infrastructure. The purpose of sponge city programs, China’s best-known adaptation initiatives, is to enable urban areas to better absorb and remove rainwater through use of green spaces, underground reservoirs, canals, and pumps. But retrofitting a city is costly, and relies mostly on government funds. Even the limited number of existing projects have thus far been hampered by financing bottlenecks.

In the Qingshan District of central China’s Wuhan, one of the earliest sponge city pilot areas, local officials told Chen that they weren’t able to complete many projects due to a lack of money. Authorities have struggled to bring in private financing. “Basically, the private sector cannot see how they can benefit from this investment,” says Chen.

The Zhengzhou tragedy has inspired greater urgency elsewhere. Beijing, for example, has run an analysis of its flood response system since then. Chen said that, if the proper policies are enacted, the city’s extensive canal system could potentially allow the Chinese capital to deal with amounts of water similar to those that fell on Zhengzhou.

But not every city is able to say that. Zheng Jiangyu, a planning official at the water authority of Guangzhou, capital of southern China’s Guangdong province, tells Sixth Tone that they are not confident the city could withstand a similar downpour. After a flash flood in a Zhengzhou subway tunnel killed 14 people, Guangzhou quickly checked its subway response system. The city has been studying how to improve its preparedness. “Since the volume (of rainfall) is beyond the standard, the city may still be overwhelmed with water,” Zheng says.

The city frequently has to deal with extreme weather. Most recently, in July, a two-year-old Guangzhou subway station was flooded by stormwater. Zheng says constant flooding incidents have prompted the city to map its flood-prone areas, and that it is now prioritizing flood prevention when renovating old neighborhoods with poor drainage.

Workers stand outside a flooded subway station, in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, July 30, 2021. Southern Visual/People Visual

Currently, China mainly relies on engineered solutions such as dykes and breakwaters to prevent floods, but this approach is increasingly being questioned due to its impact on ecosystems. Moreover, it is unrealistic to rely solely on inflexible infrastructure when dealing with an unpredictable environment, architects who work with government officials tell Sixth Tone. “Many such methods are very fragile. Once the danger is larger than the system’s limit, a system can just completely collapse,” says Zhu Zhonghui, regional director of One Architecture & Urbanism’s Shenzhen office, which has been developing the Guangdong city’s coastal resilience.

As such, there is growing interest in using nature-based flood solutions in urban planning. To better deal with high water levels, Guangdong’s provincial authorities plan to build 5,200 kilometers of “ecological belts” along river banks in the Pearl River Delta, expanding them to over 15,000 kilometers by 2030. For cities in the region, the plan presents a chance to look for alternatives to building or reinforcing dykes, says Ha Wenmei, water director at Arcadis China, an Amsterdam-headquartered design and engineering company.

Along the “ecological belt,” architects could design recreational spaces that can serve as floodplains during extreme weather, says Ha, who is involved in a Shenzhen “ecological belt” project. “During the urbanization of the past 30 to 40 years, natural ponds and floodplains have been filled up, with hard materials covering the ground everywhere,” Ha tells Sixth Tone. “This has broken the natural hydrological cycle.” While returning to the past is now impossible, the Dutch experience of making room for excess water can offer valuable experience for Chinese cities, she says. “The idea is that you don’t block the water, but channel it.”

When urban planners consider how to improve their flood preparedness, it is vital for each city to do so based on their local situation, says Li Huimin, associate professor of climate policy at Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture. Shanghai, for example, announced in 2016 that it would invest in China’s largest deepwater drainage system under the Suzhou Creek, which runs through the city center. (A spokesperson of the utility Shanghai Chengtou Water Group tells Sixth Tone that construction has yet to start.) Such ambitious infrastructure is not within every city’s financial capabilities. “Infrastructure costs a lot,” Li tells Sixth Tone. Choosing too big a project might mean funding runs out halfway.

There are also improvements to be made in how governments and people prepare and respond. The lesson from the Henan floods is that China should enhance its early warning, emergency response, and insurance mechanisms, according to Zheng Yan, professor of climate adaptation at the University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a lead author of the sixth Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report. She also noted the public should be better educated about climate risks.

Currently, very few policy packages in Chinese cities are specifically dedicated to adaptation. Instead, related measures are spread out across different documents, often those relating to low carbon programs, Li says. According to the professor, governmental urban planners’ understanding of climate risks is still rudimentary. Sometimes, they confuse mitigation — such as reducing local greenhouse gas emissions — with adaptation.

The main concern for Ye Qian, professor of climate risks at Beijing Normal University, is that 2021’s floods are forgotten. The mistake China often makes, Ye tells Sixth Tone, is “lessons learned, but never applied.”